Cooties and Careers: On Stuart Ross’ The Hotel Egypt

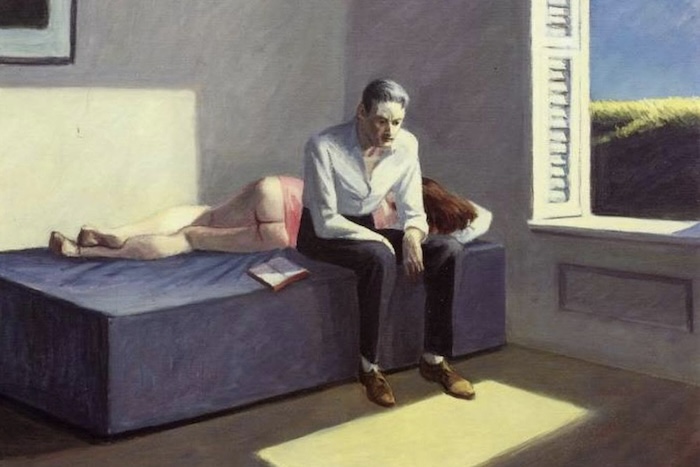

Ty Rossberg ought to try being a serial killer. He’d at least be more loved than what he is in Stuart Ross’ The Hotel Egypt: a straight white male writer during the dawn of the Trump era. While his girlfriend Jenny Marks’ new essay collection is the hottest book of the year, he is relegated to playing the once prestigious, now subordinate, role as sole breadwinner (as a management consultant). Her semi-truthful account of her abortion captivates audiences, elevating her to the “literary equivalent of the Rolling Stones, or at least the National,” as Ty snidely remarks to himself while attending her reading in Chicago.

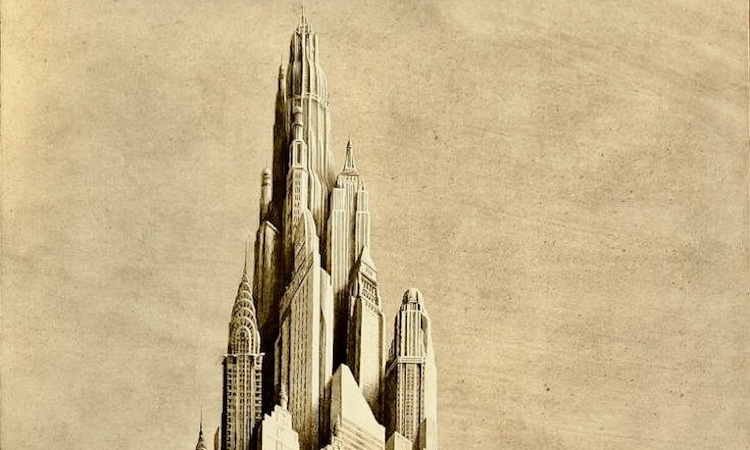

The Hotel Egypt is an exploration of a modern American man’s yearning to be needed and relevant. The results are mixed, with a relatively strong first part that wanders into the surreal and which ultimately undermines the story’s initial intriguing bitterness. In many ways, Ty has a great life: he has an apparent soulmate for a girlfriend (both he and Jenny grew up together in Queens, went to the same schools, and have similar literary ambitions), he has a well-paying career, and he lives comfortably in a desirable Manhattan neighborhood. Yet something crucial is missing in his life.