Ty Rossberg ought to try being a serial killer. He’d at least be more loved than what he is in Stuart Ross’ The Hotel Egypt: a straight white male writer during the dawn of the Trump era. While his girlfriend Jenny Marks’ new essay collection is the hottest book of the year, he is relegated to playing the once prestigious, now subordinate, role as sole breadwinner (as a management consultant). Her semi-truthful account of her abortion captivates audiences, elevating her to the “literary equivalent of the Rolling Stones, or at least the National,” as Ty snidely remarks to himself while attending her reading in Chicago.

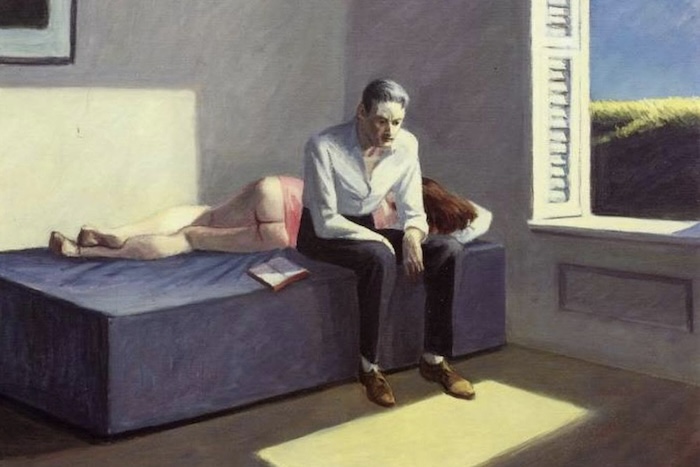

The Hotel Egypt is an exploration of a modern American man’s yearning to be needed and relevant. The results are mixed, with a relatively strong first part that wanders into the surreal and which ultimately undermines the story’s initial intriguing bitterness. In many ways, Ty has a great life: he has an apparent soulmate for a girlfriend (both he and Jenny grew up together in Queens, went to the same schools, and have similar literary ambitions), he has a well-paying career, and he lives comfortably in a desirable Manhattan neighborhood. Yet something crucial is missing in his life.

In times past, being a provider bestowed great status on a man. But in Ty and Jenny’s metropolitan, educated, upper-middle-class set, there is no glory in a stable white-collar life. In an inversion of the traditional breadwinner vs. homemaker dichotomy, it’s the latter, rather than the former, who gets to enjoy the privileges of a public life. While Ty is stuck being employed somewhere, Jenny is at home, accumulating “more social media followers than the population of an up-and-coming small town.” And when Jenny tells him that she never needed his money and she had only accepted it to make him feel good, his irrelevance is cemented.

Where the internet is our public square, the office is the new kitchen. In many online discussions, I’ve often seen women say the ideal man has no social media. But if the internet is indeed our modern public square, what does that mean for the preferred role of men in public life?

Ross strikes a good balance of making Ty irritatingly self-pitying yet also understandable. From a historic demographic viewpoint, Ty has little to complain about: our libraries are filled with the celebrated works of straight white male writers. Yet Ty is not part of some hive mind with a collective memory; he is an individual with his own dreams. And if the likes of Jenny feel that having ever been ignored or silenced — whether based on gender, race, sexual orientation, religion, etc. — was a grave injustice that warrants a ferocious uprising, then the Tys of the world would also naturally feel aggrieved when it happens to them.

The novel’s high point comes early on in a vicious exchange between Ty and Jenny, right before they break up. After Ty floats the idea of permanently staying in Chicago instead of returning to New York City, which Jenny interprets as his desire to leave her (it’s revealed he’s cheated on her at least once before), she launches into him. She predicts that, at last, he’ll be exposed as the “normie” he’s always been, falling for one of the “corporate sluts from Ohio” whom he’s always ogling. He replies by saying she seems to already have the outline for the next book, which she counters with:

Sorry you can’t write it yourself. Sorry you’re past a prime you never had. Sorry the culture has moved on. Sorry you think just because you read a year of women writers, women writers are going to read a week of you. Sorry you never figured out you don’t get to be the writer you want to be. Sorry I don’t owe you shit. Sorry you don’t know what you think. Sorry not sorry.

The harsh exchange is powerful because, at last, after nearly a lifetime of being together, Ty and Jenny opt out of passive aggressiveness and say what’s really on their minds. From such revealing outpourings, much is now in play.

Can a man stand it if his girlfriend or wife is more successful than he is? Can she? Because Ty’s biography is so similar to Jenny’s, his jealousy at her ascension is more acute. Their alma mater invites her to be a guest speaker, not him. New York interviews her and she gets to tell the magazine about her favorite stationery, which had been his dream. “[I]t was almost like fame had found me,” he consoles himself.

For ambitious and well-educated men and women who also want their significant others to be equally successful, is it best that their dreams lie in different fields? This is not only a men’s problem either. In her essay “The Lure of Divorce,” Emily Gould said: “I wondered if my marriage would always feel like a competition and if the only way to call the competition a draw would be to end it.”

And for all of Jenny’s anger, how oppressed is she, really? Compared to Ty, she may be able to claim some righteous victim status, but her critics also note that she is “a privileged white girl getting an abortion so she can have experiences to write about” (and only Ty knows that she fabricated that story). Her close friend Rhonda, who’s part of a downtown literary set (that Ty thinks hates him), is described by Ty as “another ‘shock the bourgeoisie’ white female writer who meant it, and said it, in a prep-school French.” This being the mid-to-late 2010s, it is only a matter of time before these women seem Ty-like to someone else, likely another member of their social class with a few more identitarian credentials who envies and covets their cool-girl status.

Unfortunately, the rest of the novel swerves into the quasi-fantastical where Ty immediately meets and marries a woman named Ellory, whom, I was convinced in my first read-through, was an illusion as Ty’s lab-made revenge-fantasy concoction. Ellory is the exact type of woman Jenny hates and fears: beautiful, from a wealthy suburban Midwestern family, and just intellectual enough so that Jenny wouldn’t be able to dismiss her as a bimbo (Ellory’s read 200 pages of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot). Ty and Ellory’s lightspeed romance has them married within a week of meeting, after they jet off to Rome and Athens and he proposes at the Parthenon.

Ellory is a puzzling character. She is above Ty in social status (her parking-lot mogul father buys them their first apartment and he even offers Ty a job), yet her extremely tragic sexual past gives her a damsel-in-distress quality that makes Ty feel needed. In fact, though she is quick to cheat on him after their wedding, he is willing to overlook that, even though it means that he’s not certain that he’s the father of their child:

She’s allowed to leave me, of course, anytime she pleases, but I will never let her go, even after I’ve fallen out of love with her, because I know she’s too fragile for that kind of rejection. She is a ruined subject… Sex ruined her eyes, sun ruined her flesh, sunbeds ruined her scent, tobacco ruined her lungs, cocaine ruined her nose…

Apparently, he prefers being cuckolded to being with Jenny.

I’ve never liked the whole is-this-real-or-not device in fiction. It usually comes off like a hedge by the author, like online posters who are in perma-irony mode to always have plausible deniability if their takes are judged harshly, or, worse, deemed to be too sincere. In fiction, in which authors already have the inherent burden of establishing what we all know are made-up stakes, such decoupling from consequences turns the story into the equivalent of your chatty friend telling you yet again about one of his or her dreams.

The problem is not that Ellory is cartoonish. Some cartoonish people do exist. The issue is more that nothing that Ty and Ellory do with each other seems to matter in the reality of the story. Their relationship, beyond its whirlwind timeline, is filled with bizarre events, such as when they return from their European trip and find Ellory’s elderly millionaire ex-lover, Shelly Fink, waiting for them in her condo. Shelly even beats up Ty, who calls the elderly man “daddy.” On their wedding night, Ellory defecates herself, an act she’ll repeat later on (Ty even tastes her excrement, which he says “tastes like being online”). And when he and Ellory meet a mysterious jazz musician, Moses Murray, in the Pacific Northwest, Moses keeps trying to have a threesome with them. Ty thinks he wants Moses to fuck him.

Are these all absurd manifestations of Ty’s emasculation? Are they actually his deeply suppressed fantasies? I couldn’t get myself to care when, soon after these events, Ty woke up in the Trump International Hotel (where he spends his first night after breaking up with Jenny, and also where he marries Ellory) and discovered it all to be a dream/nightmare.

Ty and Jenny actually do reconcile towards the end of the novel, where she appears to tell him what he and other guys like him want to hear so much: “I even started to think it must be hard for a white guy right now, but I quickly took that thought back. It’s always easy for the mean white guys and, unfortunately for you, you’re not one of those.”

So therein lies Ty’s predicament: he does have a lot of advantages in life and if he truly wanted to, he could press them, like in MAGA-world. But he’s not mean enough for that. He can sleep in the Trump International Hotel, but he’ll always just be a guest, ridden by guilt. He needs his hardship to be acknowledged, and after that satisfaction, he will accept his fate as he appears to do with Ellory in the final scene in which they pin their hopes of happiness on their (putative) son, appropriately named Hope. Because yes, Ty actually does end up with Ellory. That reconciliation with Jenny turns out to be a dream.

In the past couple of years, a popular (if often shallowly discussed) topic in the literary world has been the disappearance of young male writers, especially young male novelists. It’s ostensibly a niche topic, hyper-focused in the realm of literary fiction that only a bunch of weird loser freaks care about. But it speaks to the wider issue of decreasing relevance of straight men relative to straight women, and the conflicts that result from it. For instance, something like the rancorous 2016 Democratic primary battle between Hillary and Bernie made most sense to me, at least regarding its portrayal in the elite media sphere, as a white gender war between accomplished and well-educated women who felt they’d finally taken control of the Democratic Party vs. the failsons who had fallen behind. Hence, the “Bernie Bro” saga, which was simultaneously bogus but also spoke to something real.

But since writers are as needy as the most attention-seeking reality show aspirant — except instead of being blessed with unusual beauty, musicality, or athleticism, their talent is preternatural self-obsession — I wanted to pair this review with a narrative outside the literary world. I’d heard of, but had never seen until now, the 2023 Netflix movie Fair Play. The protagonist, Emily, and her boyfriend, Luke, are both analysts at a prestigious hedge fund. Because of policies that discourage office romances, they keep their relationship a secret. When a promotion becomes available, Luke hopes and expects to get it. However, it turns out that the top brass actually sees Emily as the rising star and she is awarded the promotion. As a result, Luke’s resentment and jealousy fracture the relationship.

The movie takes the easier way out by turning Luke, by the end, into a morally reprehensible wreck. It makes for an entertaining thriller but leaves some of its more nuanced aspects on the table. Notably, Luke never fully accuses Emily of sleeping with Campbell, the founding partner. His gripe is more that she doesn’t even have to, that she can use her sex appeal (not to mention her ability to provide good PR by virtue of her gender) to simply charm her way to the top in a way that he can’t. You can even sense that he’s bitter that she doesn’t have to actually have sex with the boss, which would at least degrade her, not to mention give him moral superiority in the relationship. The modern man doesn’t hate whores so much as he wishes that he could be them. It’s a form of progress.

Fair Play makes it clear that Emily is undoubtedly more qualified than Luke (he was a nepotism hire and Campbell doesn’t think much of his analyst skills), but if her gender did play at least a partial role in her advancement and she and Luke were of roughly equal ability, how justified would Luke have been in feeling aggrieved? As with Ty, from a zoomed-out historical view, the Lukes of America have had plenty of time to enjoy exclusive access in their desired fields. Emily doesn’t even confront Luke with a sorry-not-sorry speech like Jenny does with Ty; she even tries to help him get the next promotion so they can succeed together (though he scorns having to need her influence).

Would Ty, Luke, or Emily (Gould) have been more capable of being happy for their partners if they were in different fields? It’s generally easier for us to be more excited for others’ success if they’re not living our dreams. For men who strive to be more egalitarian, their true test comes in precisely this situation because it’s not the biggest sacrifice to be supportive of women with whom they don’t feel in direct competition, and in fact, there are personal rewards for doing so. Case in point: American men who bemoan Western feminists while becoming champions for women’s rights in foreign countries (their zeal often directly proportional to how attractive they find these foreign women). It’s peacocking, liberal-male style. But what about when it does become a zero-sum game, one that women have had little choice but to lose, time and time again?

If one has an obsessive will to excel in a certain endeavor, wouldn’t their soul mate share that same obsession? Or does thinking so place too much emphasis on one’s romantic partner to fulfill all of one’s needs, whether they be emotional, spiritual, or sexual?

Both The Hotel Egypt and Fair Play address these contemporary gender relations issues, albeit with their own flourishes, the former with a surreal approach and the latter with a thriller-like one. Ty laments that his own life, unlike Jenny’s, consists of “unmarketable suffering,” and when he says to Jenny that “[their] lives aren’t material” for her to write about, what he’s more upset about is that only she gets to mine her experiences for an audience. He has to hide behind fiction, because nobody wants the real him. For that matter, nobody wants the fictionalized him, either. And if there’s something wrong with inserting extremely dramatic events into a story to make it more marketable, then we should all impugn Dostoevsky, who said he centered Crime and Punishment around an axe murderer because he had to get people to actually read his story.

Still, do you know what would actually be more bewildering than The Hotel Egypt and more gripping than Fair Play? A narrative in which the mundane yet monumental problems arising from the perplexing re-negotiation of modern heterosexual relationships were scrutinized, from start to end, with no off-ramps to emotional safety.

Chris Jesu Lee lives and works in New York City and has previously been published in The Believer, the Cleveland Review of Books, and Current Affairs. He writes the Substack newsletter Salieri Redemption.