Lubbock, Texas is almost exactly five hours from Dallas, Albuquerque, Oklahoma City, and El Paso. It’s home to Texas Tech University, the National Cowboy Symposium, and frequent dust storms and tornadoes. In 1951, the still-unexplained “Lubbock Lights” sightings helped to kick off the UFO craze. In 1988, 12,000 pilgrims came to Lubbock to witness an alleged apparition of Mary. In between these two phenomena, a young man named Terry Allen left Lubbock for California. He wanted to become an artist, but he wound up becoming something more.

Allen is perhaps the only person in history to achieve equal acclaim in the fields of conceptual art and country music. His work hangs in major museums and his public installations can be seen livening up the staid financial districts of major cities, while his weird, warped, and warm brand of outlaw country, to his devoted cult, stands shoulder to shoulder with Willie, Townes, and the rest. Brendan Greaves, who through his offbeat, literate “American vernacular” record label Paradise of Bachelors helped to rescue Allen’s music from defunct-label oblivion, spent five years talking to Allen, his friends, and his collaborators to produce Truckload of Art, the first major biography of him and his work. For anyone with an interest in any of the things I mentioned above, it’s essential reading: as a record of a truly underappreciated American artist, a narrative of a biographer coming to know his subject, and an exploration of the perils and joys of a creative life.

If Terry Allen’s upbringing was a novel, James Wood would condemn it as West Texas Hysterical Realism. He was born to Pauline Allen, a charismatic, alcoholic roadhouse piano player, and Sled Allen, a former minor league catcher-turned-local wrestling and event promoter. Four-year-old Terry, between matches, would stride into the ring wearing a cowboy outfit and demonstrate his pint-sized moves. A few years later, he watched from the wings as his father brought acts like Bo Diddley and Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys to Lubbock. He raced cars, skipped class, drew and drew, banged out songs on his mother’s rickety piano, and dreamed of escaping the flatlands. Then Sled died, Pauline slipped away into drink, and Terry, numb and drifting, headed to California to become an artist.

Greaves spends a hefty first third of the book detailing this period of Allen’s life, venturing far backwards into some shockingly macabre, Faulkner-esque stories of his ancestors. At first, it seems to the reader like the typical biographical vice of research for its own sake, but it slowly becomes apparent how his family history and early life, which Allen would later revisit in ongoing projects like DUGOUT and MemWars, are central to his practice. Allen in his later career is an artist of memory, particularly in his intense, fragmentary poetic writings and his installation work, which often takes the form of ghostly motels, bars, and bedrooms, seen through the mist of recollection. But all that would come well after he escaped Lubbock and created the work around which much of his later career orbited: JUAREZ.

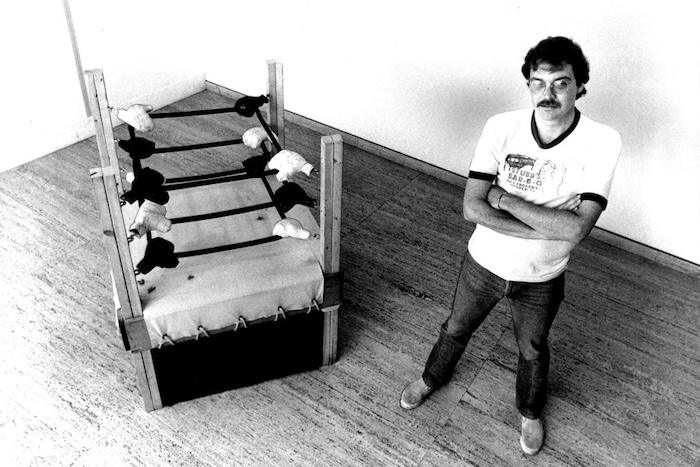

As a student at Chouinard Institute (later CalArts), Allen, leafing through a 1948 book of architectural history called Mechanization Takes Command, came across an antique patent for a machine intended to facilitate the butchering of hogs. This machine inspired a later sequential drawing in which this cold apparatus operates upon a group of indistinct, psychedelic Western figures. For reasons unknown even to himself, he called this drawing The Juarez Device. From this single spark of inspiration grew JUAREZ, an ongoing, ever-changing multimedia conceptual artwork that has lurked on the edge of his life ever since, sometimes growing and sometimes receding, but always present.

JUAREZ is, as Allen calls it, “a simple story.” It concerns two couples: Sailor and Alice, a young American serviceman on leave and his teenage bride from Tijuana, and Jabo and Chic, a petty criminal from Juárez and his witchy girlfriend. Sailor and Alice elope to Cortez, Colorado, where they encounter Jabo and Chic. There is an argument, and Sailor and Alice wind up dead. Jabo and Chic then flee back to Juárez, where they find themselves metamorphosing into strange doubles or reincarnations of their victims.

This is the basic structure of JUAREZ: a variation on the murder ballad, one of the oldest American song forms. But it’s a slippery story: details change, characters seem to swap identities, and the motive for the murder at the heart of the story is never revealed. It feels mythic, archetypal (“Myth, my ass” is Allen’s exasperated comment on this common reading, but it’s out of his hands now). It seems, like many great stories, to have been sitting there in the collective unconscious until he happened to be the one to pick it up.

For that reason, there’s no definitive JUAREZ. Over the course of Allen’s career, it has been a series of visual artworks, an experimental theatre production, and a radio play. But its most enduring version, as much for ease of access as for quality, is its 1976 incarnation as a concept album. There must have been something in the water around that time, because Willie Nelson released his classic Red-Headed Stranger, another sparse, haunting narrative album about a murder and a flight from the law, only months before Allen released Juarez. (For stylistic purposes, Juarez refers to the album while JUAREZ refers to the larger, lifelong project). But I’ll stand on Willie’s table in my cowboy boots and say Juarez is the superior work. Armed with nothing but a piano, his inimitable West Texas whine, and the occasional ghostly guitar accompaniment, Allen spins a fractured borderland tale suffused with black humor, sexual frustration and terror, and a final melancholy wistfulness.

After Juarez, Allen convened a full band for his most popular and enduring record: 1979’s Lubbock (on everything). A double-LP magical-realist West Texas reverie, Lubbock is relaxed and expansive where Juarez is alienated and nervy, full of love songs, tales of chance encounters, and half-ironic shitkicker sneers—its leadoff track “Amarillo Highway (for Dave Hickey)” is almost certainly the only song dedicated to a maverick art critic to get regular play on country radio. With its tongue-in-cheek songs about the art world side by side with tales of beautiful waitresses and football players gone to seed, it’s the fullest example of Allen’s range as a storyteller and his ability to cross worlds. Though his music is often sardonic and dry-humored, there’s an essential warmth and sincerity to all of it; for a guy who went to art school and loves Barthes and Artaud, there is no sense of an intellectual’s removal or ironic distance in a record like Lubbock. It simply is what it is, a classic country record and a kaleidoscopic portrait of a West Texas town, which, like a Victorian novel, contains within a small space the entire human comedy.

More work and more music followed, as Allen found gallery representation, was selected for grants, and carved out a stable career as a working artist. While he continued to regularly record (and could still write an earworm like 1983’s “Gimme A Ride to Heaven”), his work grew more autobiographical, delving into his childhood and family life to arrive somewhere between memoir and tall tale. His installation works ventured deeper into his subconscious, as in works like Ancient, a part of the DUGOUT series exploring his family past, where a taxidermied coyote wrapped in neon tubing stands on a wooden ledge, like some numinous dream guardian. He also began producing radio plays and sound collages: strange, oneiric ambient country narratives suffused with melancholy and loss, bearing titles like Torso Hell and Bleeder. Truckload of Art ably documents this lesser-known stage of his career, which culminates in Allen reaching a new generation of fans, as a result of the 2016 reissue of his early music by Paradise of Bachelors, his 2020 record Just Like Moby-Dick, and the decision to publish the biography itself.

Through the epic scope of the book, certain names appear again and again. First and foremost, there is his wife, Jo Harvey. A poet and actress in her own right, memorably appearing as the Lying Woman in True Stories, Jo Harvey and Terry were high school sweethearts in Lubbock, got married at age nineteen and have been together ever since, with Jo Harvey uprooting her life in Lubbock and following Terry to California. The book is unsparing in depicting the difficulties of both their creative and conjugal relationship, but they have persisted as a stabilizing force in one another’s lives in a way rarely seen in the tumultuous field of artist partnerships. There’s also Allen’s relationship to his oddball Texas songwriter peers, particularly Guy Clark, as well as Joe Ely, Butch Hancock, and Jimmie Dale Gilmore, a.k.a The Flatlanders, who were just a few years behind Allen at Monterey High School and released one perfect album of mystical, haunting country ballads before going on to long solo careers. There’s his distinguished comrades in the West Coast fine art scene, Ed Ruscha and Bruce Nauman. There’s David Byrne, who formed a bond with Allen despite their differences in temperament — urban and tight-wound versus rural and louche.

And there’s Dave Hickey, the brilliant art critic and writer who championed him for his entire career and remained one of his best friends until his death in 2021. All artists have a network of friends and collaborators, of course, but Allen’s is especially strong and varied. One gets the sense that it is his openness to these collaborations, to flitting between genres, mediums, and social circles while maintaining the stabilizing force of Jo Harvey and his two children, that is one of the keys to his artistic vitality and versatility. And though he has his moments of spikiness and irascibility like any artist, from reading what everyone in Truckload of Art has to say about Allen as well as Greaves’ own reflections, it seems that he has been able to keep these social circles from dissolving because he is at bottom a fundamentally warm, decent guy.

I came to Truckload of Art as a huge fan of Juarez and Lubbock and came away reeling from the dizzying vitality and variety of Allen’s work, in drawings, public art, and performances as well as music. It’s the nature of a career like his to defy easy cataloguing, and much of his non-musical work lingers in archives, in private collections, or simply in memories, which makes it difficult to approach his body of work as a whole, unified as it is. With this biography, Greaves has performed an important service, helping to bring together the different threads of Allen’s work so his fans can finally see the entire tapestry. With any luck, the book will cement a place for its subject as a member of that rarified circle of American artists who have spent long careers in multiple mediums trying to show us something deep, wild, and ultimately true in the country’s unconscious.

Henry Begler writes the Substack newsletter A Good Hard Stare. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.