It was a bad break, a slip and then a tumble. Denny had been jogging (jogging!) for the first time in what felt like ever, trying to be healthy now that he’d turned thirty. Middle age was coming. So was the pothole right off Fillmore on the nice block of Marine Parkway, with all those houses he’d dreamed of selling, hoping to jumpstart his middling realty career. Maybe his eyes were on the good roofing and that’s why he planted awkward, landing strange on his ankle, turned it, heard the snap, and if he’d been in any state of mind to pick his (never specified) emergency contact he would have gone for his stalwart older brother Jim. But instead, due to proximity, it was Tiny.

Denny had never gotten along particularly well with Tiny, his younger brother. Was it something from childhood that they never put past them? Denny could hardly remember. A prank with a Lego block that brought punishment to Tiny but not to Denny, then their mother’s favorite, at least that’s what Tiny said years ago, deep in Christmas Eve drinks. He was a science teacher at a Manhattan middle school, always sullen even in the summer. Denny and Tiny lived not thirty blocks apart yet rarely crossed paths, not since their mother had retired to North Carolina and suggested they sell the old house (Denny obliged) to help them all get a leg up in life. Denny saw more of Jim, even though Jim was on his third kid and second marriage and busy a borough away in Queens. Yet here was Tiny riding with him in the ambulance, shaking his head and making gruesome faces at the break, looking at his watch in a way that Denny felt was far more than necessary.

But what was the saying — atheists, foxholes? It was a strange illumination for Denny. The ankle would heal with a cast, the doctor told him that night, already half pulling off his plastic gloves before leaving the room — but he’d have to really keep off his feet for a while. You don’t realize how shitty it is to be bed-bound until it happens. On his couch, Denny read the real estate listings in the Times and the Journal. He flipped through different channels on his foggy TV. Yes, Jim brought some magazines and Denny’s nephews for a quick Saturday visit, but other than that he had some phone calls from his mother and friends. And Tiny.

Every afternoon around 4 pm, Tiny let himself in with Denny’s welcome mat key saying nothing, pulling up a chair.

Yep, he’d grunt eventually. You got your etiolating done, and looks like there’s a good de-swelling operation going. He fancied himself, because science teacher, something of a medical and academic expert, which Denny had always thought was ridiculous.

But ridiculous was all he was getting and so he found himself grateful for it. His brother would stay there in a folding chair for hours — whole hours — asking only if they could put the volume up on whatever stupid sitcom was playing. Then at 8, after arrival of a takeout dinner that he didn’t touch, Tiny would leave. Well, he’d say. Then his dumpy back.

We can eat together, you know, Denny said once.

Tiny at the door scratching at his jeans. Yeah no worries, he said. I actually got a certain someone back home these days.

Denny pulled his head back against the couch pillow. A girlfriend, he said?

Don’t sound so overjoyed, Tiny said. His face was patchy with color. Just trying something out. Actually she told me I should help you, so count yourself lucky.

Denny had never heard about relationships from Tiny, the polar opposite of Don Juan Jim. And he knew Jim didn’t hear about that kind of thing from Tiny — they hadn’t been close since adolescence. Maybe his expression of surprise cast a wound.

That’s the last we’re talking about it, Tiny said, I mean it. He pulled the door shut.

But Denny guessed Tiny really was trying to impress the woman or whatever, because the next week, when Denny had a followup doctor’s appointment, it was Tiny who drove him there and home. From the front seat, Tiny noted darkly, I guess I gotta be driving you to work then.

Denny waited but couldn’t think of an alternative, at least for the mornings. It was his accelerator leg. Yeah, he said. That’s good. Ok.

They had never done the crucial work of building a friendship, apart from blood. They had hardly spent time alone together, without their mother officiating. Jim could talk to anyone, had a fun way about him, was a television producer on a third-rate reality TV program. Not exactly Hollywood, but at least he was pleasant, or so Denny felt. Tiny was a pill, no other way to put it.

But it was Tiny now. Every morning Tiny drove Denny the requisite ten minutes — it was five minutes out of his normal way, Tiny said grumpily — and then U-turned around to hit Ocean Parkway and catch some green lights north. Tiny always said the same thing when Denny hobbled out of the car: Take care. Denny realized eventually that it was something their father had said reflexively, to friends and family, in greeting and in the middle of sentences, in the days before he hightailed it to wherever or California.

One day, when Denny had a long day of real estate ahead, when he was head-prepping for hobbling around on his cast, he finally pulled his gratefulness together into a bundle and said to Tiny: I really appreciate this, you know the driving and everything. Whether or not your, you know, ladyfriend told you to do it.

He felt better the moment he’d said it, the one good thing he would do in a day soon to be wasted with post-college brats looking for railroad two-bedrooms, or harried families hoping they could get their offer in early, because the place was so perfect for them, you know? He knew the lines he needed to say. He knew how to keep the rope of life moving forward. But little catastrophes have a way of encouraging finer emotions.

Tiny grunted. You’re welcome, he said. And then, because he was Tiny, he added: It’s just ironic, ya know.

Denny turned towards him. What’s ironic, he asked?

Tiny paused for a moment to flip his blinker on, then: Ya know.

Nah, Denny said, the accent of his youth rising in him. I don’t know.

Well, Tiny said, a ripped smile on his face. I just wonder where you were when I had my issues with college.

Denny leaned back, scratched his cast.

Tiny had been the only one of the brothers to go away to college. It was the usual sibling progression. The oldest is the most outgoing, bold and dashing. Jim had hopped right into PAing for the TV industry in the city. Denny was an ok student and thought he’d go to one of the CUNYs. The commute to Baruch felt like a treat. But Tiny had for a brief period set his sights higher. He had wanted to go upstate to school, to Binghamton.

When Tiny successfully gained admission — apparently he was fairly smart — Denny remembered being a little sore over the fact that his mother literally organized a party for Tiny, a barbecue in the backyard. She’d even — and this was incredible — given a speech about how proud she was of her youngest and how he was on to great things, perhaps he’d even be an astronaut. Tiny had a thing for space travel and their mother — Jesus, it came back — was always repurchasing the same science set for Tiny even though Denny’s own request for goalie gloves went ignored year after year.

At the party, Jim came late with his briefly-fiancé Terry Anne (model-scouted, actress, took cabs, it was never bound to last long, even for Jim) and before he left presented Tiny with a check for $2,000, a godly sum to help with tuition. Tiny’s real name, Timothy, not the old childhood moniker they had given him, grownup and official on the line.

Denny didn’t think he went with Tiny to move him into his freshman year dorm. He’d been mostly free but he made some excuse about an important job fair that he wanted to attend. As Denny recalled it those first few school months really cemented the way things were going to be between him and Tiny — they never spoke, not by phone or email, though Denny was apprised of his younger brother’s successes by his mother and, more annoyingly, Jim. Denny knew that Tiny was excelling in his introductory astrophysics class that an adviser advised would be amenable to NASA. Most shocking was that Tiny really seemed like he was heading towards achieving that dream.

It started to fall apart that spring, as Denny was set to become a senior. It was around when Jim and the briefly-fiancé inevitably broke it off, something about her haughtiness and his cheating with a Law and Order PA. Their mother lost her job with Catholic Charities when the church faced economic uncertainties stemming from what she always called its “young man problem.” And Tiny’s financial aid suddenly turned into student loans.

It was a precursor to the financial crash that would occur a few years later. Binghamton said some mumbo jumbo about fewer scholarships, and they quoted him a number that was many thousands of dollars too high to earn in a summer of working as a lab assistant alone.

Denny remembered the issue coming to him from his mother. He was quite sure Tiny himself never brought it up. But the request arrived that he, Denny, the middle brother, postpone his final year of college and continue the summer job he’d landed, with a real estate broker on Staten Island, and help his younger brother stay at Binghamton.

It should be noted that driving was important here too. Denny was living at home, and didn’t have a car. The job was a hike. He had to get himself to Staten Island every morning by 9 am. This was a serious thing from Marine Park: the bus to the Junction. An hour’s ride to South Ferry. The choppy water. The job was easy but banal. For the first time in his life he couldn’t wait to get back to school.

Denny told his mother he couldn’t do it. He had to take care of himself.

He remembered the look on her face when he announced his decision. They were having dinner, just the two of them. The look was blank. They sat in silence, and eventually she responded: Someday you’ll start thinking about other people. He was so stunned he left the room.

She came up to apologize later. She leaned against the doorframe and said she got it, it was a not-great job (he prickled a little), and it was a lot to ask to support a younger brother, particularly given the state of their relationship. (This surprised Denny too. He’d never thought about their “relationship,” baby nicknames and fights notwithstanding. They were just brothers.) She knew he had to do what made sense for him. She sighed. Here Denny stood up and considered giving his mother a hug, but there was something strange about it. Instead he stood in the middle of the room and said: Tiny’ll be ok Mom. He knows what he’s doing.

You’re right, Denny said to Tiny in the car all those years later. I wasn’t there for you.

Tiny grunted. Denny realized that a grunt alone couldn’t wipe away the last ten years — the fact that Tiny had dropped out of Binghamton, gone to Brooklyn College. Though he got very good grades he never nabbed attention from NASA. The one helpful professor in the hard sciences department encouraged Tiny towards a teaching program. Tiny settled for the education coursework and got used to PTA meetings, field trips, state exams.

There was a time when Denny had thought of the story as bleak, when he thought of it at all, bleak in the way of his own trajectory — the fact that despite having finished his senior year at Baruch on time and uninterrupted, he still did not get a better job than the one he’d had the summer before. He was too exhausted to see friends or potential girlfriends, let alone his brothers — though Jim, bless him, always dragged him out for a night on the town. Tiny went his own way. Eventually Denny moved to his current storefront real estate firm in Brooklyn. It was all very regular. Given the surprise of Tiny’s ankle-niceness, Denny wished there was something he could do.

We can start over, he said to Tiny, shifting awkwardly to look his brother straight in the eyes.

His brother met his gaze as he put the car in park. He scoffed like Denny was crazy. They’d arrived at the real estate office. Ok, Tiny said. It’s all good man. Have a good day at work. Denny got out.

He made it through the week as usual. It was alright. Everyone assumed that he was still too infirm to really pound the pavement renting out apartments. It wasn’t yet the busy June season, when everyone was graduating and wanted to move to the city. He took a car service home at 5 pm.

All day he pondered his brother, something he’d literally never done in his life. Perhaps he did owe Tiny something. When he got home that Wednesday he picked up the phone.

Tiny answered somewhat sullenly. Denny could hear a TV in the background, perhaps a female voice? Even having heard about the new lady he was jolted. He had never pictured his brother with a woman. You have a second, he asked?

Tiny waited. Yeah, he said eventually. What’s up.

Listen, said Denny. What are you doing this weekend? He paused into the silence, had the feeling that Tiny was considering whether to invent something.

Not much, he said finally. Had some plans with . . . but I guess they’re cancelable. How come?

Listen, Denny repeated. I’ve always wanted to do this. Why don’t we go to Cape Canaveral and the beach?

He went on to explain that he had a bunch of points saved up and he could get both their flights and hotels, his office had a huge Best Western discount. It was a slow week. Wouldn’t Tiny want to see the NASA sites? They could split the rental car and maybe take off a day on Monday, give them some legroom, so to speak?

There wasn’t an immediate response on the line, and Denny could hear once again the surprising female voice in the background. Could it be that she was singing a song? Then Tiny: Assuming you need me to drive and help you move around.

Denny almost said to forget the whole thing.

Yeah man, he said. Guess so.

But it was as if the little flare of emotion in his voice was all Tiny had wanted. Sure, Tiny said.

He hung up.

They had traveled together briefly as children, the four of them, brothers and mother — Jim had always been the one to fill the role of father on such excursions. A cruise that left out of Louisiana (cheaper). A guided tour of the Grand Canyon (won at their mother’s work). A beach house rented with a man who was supposedly a friend in New Jersey, who Denny now knew must have been an attempt at a dating life for their lonely mom. On the beach house trip, Denny and Tiny got into an enormous fight over the second tennis racket and who got to play against Jim. Denny remembered (winced) that he’d taken the first swing and cracked Tiny in the head.

These memories came back to Denny slowly, and each one made him more uneasy about the trip ahead and more embarrassed about his performance as a sibling. Strangely though, when Friday arrived, Tiny seemed to be in a good mood. He shared his bag of pretzels after Denny downed his on the airplane, said that salt was good for bodily recovery. Tiny knew (or bullshitted) all sorts of things like that from a lifetime of science lessons. He asked if Denny wanted to share his earbud when Denny’s TV turned out not to work, though Denny noticed that Tiny discretely wiped it after Denny handed it back. When they picked up the rental, Denny crutching to the counter, the rental woman asked if they wanted two keys, and Tiny said no, his brother wasn’t a driver, if you know what I mean, and somehow it was a strangely sexual comment, and the woman laughed and put her hand on Tiny’s arm. You New York boys, she said. Denny felt a little silly trailing his younger brother who was carrying both their bags — but as they got into the car Tiny said, Just kidding. Sorry.

The Florida roads unspooled before them, and it seemed to Denny that his brother was taking the few curves pleasantly fast in the southern dark. They couldn’t figure out the air conditioning so they drove with all four windows down and the muggy dank slapped at their faces like a palm frond. It was only them in the left lane, and Tiny was flying, he really was. It’s good to get out of New York for a while, he said, explaining his exuberance.

Seriously, said Denny.

At the hotel Denny had expected two twin beds, but as they key-carded into the room he saw that it was only an enormous king. Tiny didn’t seem to notice or care. When Tiny grabbed the remote after coming out of the shower, he put on a National Geographic show about forest animals. Denny was pleasantly surprised. He’d never really thought much about what his brother did for fun.

Oh this is a good one, Tiny said. It’s got arachnids. Denny didn’t much like spiders but he watched for a few minutes and then closed his eyes. When he woke up hours later the TV was still on with volume lower, Tiny bundled under the covers in the chill air conditioning. The white sheet over his head like a funeral shroud. Denny turned off the TV and faced the opposite direction. They fell asleep in the same bed.

But in the morning, Tiny was agitated. It started with a phone call that woke him (them) at 8 am, a blaring goofy tune that it took Denny a moment to realize was Star Wars.

Tiny slapped at the phone until he had it to his ear. Hello, he grumbled. Some indecipherable stuff. Denny couldn’t not notice that his brother had turned his body towards the wall, away from Denny.

I told you I’m busy with Denny today, Denny heard. Can’t you just text.

More: Yeah ok.

As Tiny took the phone away from his ear Denny could for a second hear the chirping of the voice on the other end, that female voice.

Who was that, Denny asked innocently.

Tiny mumbled and rolled over. I said we’re not discussing it, he said.

Denny could see that this bad mood wasn’t going to lift when they finally went down to catch the end of a continental breakfast. Denny tried to engage his brother in planning talk but all he got was the old grunts.

It wasn’t a beach day so there was nothing else to do but go to Cape Canaveral. It felt a little silly now that they were close to it but this is why plans and discussing them and sticking to them are important, Denny had always felt, not that this had ever worked in his work life. His plan had been to use this weekend to start again with his brother.

Do you ever think, he started, what it would have been like if you did the whole astronaut thing?

Tiny laughed and it wasn’t bitter but it also wasn’t particularly heartfelt. Sometimes, he said.

Denny wasn’t satisfied. I mean, he said, it seems like kind of a crapshoot to actually make it all the way, but what if you had moved down here, got a job as a janitor, started moving your way up until you were a flight director?

Essentially all of Denny’s knowledge of space came from Apollo 13.

Tiny laughed, and it was much freer than Denny would have imagined. He felt a slight twinge that his vague needling wasn’t unearthing anything.

Yeah, Tiny said. I dunno. I’ve had other things that were a bigger deal.

Really, said Denny?

Sure, Tiny said.

Denny let half an exit go by before he went back at it. Like what, he asked.

Well, Tiny said, and then he laughed. It’s that — and then he giggled again. Denny was taken aback. He’d never heard his brother giggle before.

What is it, Denny asked?

It’s just so weird to say it out loud, Tiny said. What the hell. What’s the difference at this point. Basically . . .

And then Tiny launched into a story that Denny had never heard from his admittedly least-favorite brother. The story was about Tiny and their brother Jim’s one-time fiancé, Terry Anne. Terry Anne was someone Jim had worked with on one of those early Queens movie sets, and it was not just from her looks and rigidity that you knew she was destined for greatness. She came from a better situation and she would further it. She grew up in Forest Hills, where cars could not park and trees covered the Tudors. She played golf — golf! — with her father on a course in Nassau County. Needless to say she looked stunning. Jim once said that when he was lying next to her (this was one of those personal admissions that Jim could so easily offer, which endeared him to Denny) he found that he had difficulty controlling his breathing, so nervous was he about himself. Was his breath ok? Would she find him dull and plebeian, he who did so well in front of a barroom crowd but became flustered with books, artwork, debate techniques, facts?

Denny remembered now, now that he thought of it, that Terry Anne was in a way the beginning of the Jim-myth in his head, even though their engagement lasted less than a year. Jim had always been the fun older brother but Jesus Christ, if this was the company he was keeping, what a man he had become. She was a key mix of austerity and also politeness that rhymed with friendship. There had been a get-to-know-you dinner with her and Jim at a place with white tablecloths in Long Island City and she kept wiping a small corner of her mouth with a napkin, glancing over at Denny. Over and over, until he realized she was telling him there was marinara sauce on his cheek. He wiped it away. He had never met anyone who was subtle before.

This was the way Denny remembered it all, down to the kind of melancholy he felt when Jim said Terry Anne had returned the ring (that action, no other), and therefore was leaving their regular life forever. In some ways he’d always expected it. It was too good to be true. Jim in the end did turn out to be a womanizer.

Tiny, apparently, had a different experience. As they drove closer and closer to Cape Canaveral he never looked over at Denny but he continued talking, starting with the fact that he’d originally hated everything about Terry Anne. He said that he’d always prided himself on being the smart one in the family (no offense, he added), and he understood immediately that this shrewd creature was a match for his own wit. She had imbibed books and history from Johns Hopkins summer camps and long hikes with her Cornell-educated father. Tiny was tough. He was self-taught. He stole books from the school library and the bookshelves of friends’ parents. He gravitated toward science because it was the most obviously rigorous subject in their crappy middle school, and a teacher there had once passed out a flyer about going to “space camp” for the summer. The teacher took pity on Tiny’s lack of ability to pay the attendance fees and one day, brought him to the Liberty Science Center on a weekend. Tiny doubled down on his Regents studying and became the first person in the history of their high school to get a perfect score on every one.

He was an autodidact; Terry Anne was effortless. Even on the night Jim announced their engagement to the family (their little family), quick and breathless given that they’d met just a few months before, she had used a word Tiny had never heard of: espalier. To train (a tree or shrub) to grow flat against a wall. These bannisters, she said of their shitty crooked wooden ones. They look espaliered. He ran upstairs to the family computer on the false premise of going to the bathroom to look it up. When he came down she was still by the banister and he said the curve of the handle at the end reminded him of a cabriole, on the leg of a French-type chair. Jim, returning to the room with drinks, asked him what the fuck he was talkin about, you using big words again? (Jim and Denny did have a dickish streak, it was true.) Nothing, said Tiny, just defenestration, and he rolled his eyes towards the window. Terry Anne laughed in a startled way. She clutched her throat and stared in his direction for an extra moment, accepting the wineglass from Jim.

Yes, that night, as Tiny dreamed or simply thought, it was her face that appeared, her long and elegant golf-honed limbs, the dress she’d been wearing, white and shapeless and with a weird floral affectation on top but Jesus, she was beautiful.

Later that summer, when Jim took him to set up his first bank account ahead of freshman year at Binghamton, it so happened that Tiny found himself in the backseat of Jim’s car with her. Their mother was in the front because Jim often took it upon himself to get her out of the house (no husband). It was impossible for Tiny to ignore that something was amiss between the couple, and at one point Terry Anne sharply demanded that Jim turn off Z100’s stupid Elvis Duran Z Morning Zoo show. “So childish,” Terry Anne said.

“Well that wasn’t very nice,” Tiny’s mother said under her breath. Of course they all heard it. Terry Anne turned towards the window and didn’t respond.

Just before they left the car Tiny did something like sleepwalking. He couldn’t believe afterwards that it had happened. Slowly he hovered his hand, under the radar of the mirror in the front seat, and without looking at Terry Anne he rested it on her knee. He felt her jolt and look. He didn’t know what the hell he was doing. But then he felt the cool and comforting presence of her hand on top of his.

They didn’t exchange words or glances for the rest of the afternoon.

But over the next few months, with Tiny up at school, they began emailing. Innocent enough — just saying hi and checking in, telling her about his newer classes, relaying the academic repartee that was now his common and well-earned tongue. She told him that she sometimes wished she had gone the college route, that the movie world was heartless and always skin-deep. It dawned on him that she was merely a few years his senior. They never talked about purported wedding planning (it was expected to be a long engagement) or Jim. Instead they realized they both had the same curiosity about strange issues — the history of the Merritt Parkway or the possibility of water on Mars. She made him, over and over, explain in short paragraphs his learnings in physics and biology. She told him she’d never been in a lecture before. She was the only one in his familial circle who talked about things, and not just plans or happenings. She was something new — a mind, a presence, and Tiny found that none of the young women he met at Binghamton could compare.

Then he was informed by the college that he would not have financial aid the next year.

It was a crisis but it seemed to him that no one was all that concerned. His mother ventured that he might stay local and live at home, go to a city school like Denny. Jim said he was sorry, but there were other things on his mind. Terry Anne talked him through the experience, said she was sure someone in his family should help. Or — she ventured her own family. No, he said, he couldn’t. But the idea was sustenance even so.

It will be ok, she said, in the one late night phone call they attempted. Jim, it appeared, was out of the apartment on business. Her voice breathy and pajama’d. Can’t wait to see you back here.

And so it was anguish and excitement when Tiny returned for spring break. Though he was staying back at home in the old bedroom next to Denny’s his first stop was in Williamsburg, to visit (supposedly) Jim. Terry Anne had ordered Mexican food, she greeted him at the door just behind his brother. Her eyes lowered. They talked about ways he could save enough money to go back in the fall and Tiny got drunk, drunker than ever. So drunk that he eventually had to lie down on the couch, head spinning, he’d had hardly a thing to eat.

He woke up feeling something over him. Her loose and treacherous hair, her thin indented lips. Her eyes were wide and they grew larger. She put a finger to those lips. They kissed.

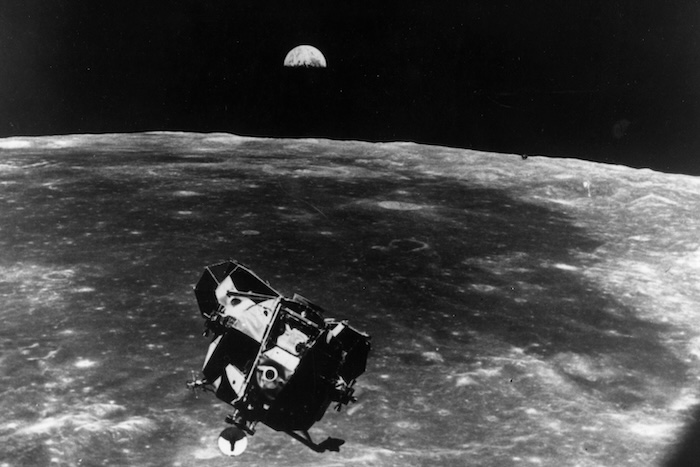

It was the first time and not the last that week. Jim was always leaving for “a business drink,” really assignations with the new woman on set he’d fallen in love with, so soon. Tiny was wrecked. He was also flying. It reminded him of something he’d learned about the early astronauts back when he still wanted to become one (what a childish dream, now he had truer passions: love and a woman), the idea that they were sequestered for a full week before gravital escape. This was so they did not catch anything communicable, whether from wives or children. Tiny felt that he was thus sequestered, behind a plastic barrier, even when talking to those he’d known all his life. There was only Terry Anne.

Denny was astonished. He ended the pretense of staring wide-eyed at the useless road. Jesus, he said. No one knew?

Tiny shook his head. Then he shrugged. They were never going to actually get married, he said. I definitely didn’t help slow things down. But I wasn’t thinking about anything else back then. It was one of those . . . all-consuming things. I rationalized. The only hope I had going for me was going back to Binghamton, like I could be up there apart from Jim and you all, and she could live there with me, and we could be together, and no one would know.

Denny leaned back. Jesus, he said.

I know it doesn’t make much sense, Tiny added, but I thought that getting away would fix it all somehow. And then the . . . money didn’t come through.

Denny felt the gut punch. His complicity at last. His first impulse was anger. But he swallowed back his words. I know, Denny said. I’m sorry.

Tiny shrugged. My thinking was, he continued, that even if we could be there for the next semester, let things cool off a little, we’d come back and could re-enter the family. That Jim would’ve been off with one of the interns and forgiven us. But we couldn’t do it. We were always hiding around in different parts of Brooklyn. And then Jim found out, too soon.

Denny waited for more but Tiny was silent. What happened, Denny prodded.

Tiny hesitated. It threw him for a spin, ya know. So to speak.

Soon, he added: He hasn’t talked to me since.

It was around this time or a little after that they arrived at Cape Canaveral. It was ridiculous, but here they were and there was nothing they could do but turn back or go forward. They sat in the parking lot with the windows down until finally Denny said, Let’s at least check it out.

It was a hot day and they got right on the tour of the gigantic hangar, where one after another of the old space vehicles were stored. The attendant offered Denny a wheelchair, he stored his crutches. Despite the wretched atmosphere, Denny felt high or intoxicated experiencing the absurd scale. Their small human bodies next to these feats of engineering. They talked more about the old history — how Tiny and Terry Anne broke off, they just couldn’t do it. How Tiny nearly told their mother once but then swallowed the story, not knowing whose side she would take. How he could never visit when Jim was there, how the few times it happened except on neutral holidays Jim would abruptly leave. How Tiny burned. How, just this year, he’d run into her at a Film Forum documentary screening, she looked drawn somehow but beautiful. He melted. The estrangement had already happened. Her acting career had sputtered. They started meeting for coffee. She stayed over some nights now, it was terrible and life-giving and strange. They didn’t exactly know what to do.

At first Denny thought that all this sharing must be healthy, and there was beauty in truth, or something. But now that he knew the story, he only felt numb. It had not changed anything, just explained. The numbness increased as his brother pushed his wheelchair around. It was the only way they could move easily. He’d thought this wouldn’t be a big deal but somehow the fact that he could only turn and crane his neck at his brother, that he was dependent on Tiny for mobility, pushed them back into their old relations, the story and air-clearing disappearing. Denny tried to reestablish equanimity. But he couldn’t. The history of three full decades of misadventures between the two of them weighed him down.

They sat in a freezing IMAX theater and watched, inexplicably, a movie about elephants. Denny had hoped that it would cheer Tiny up but in the handicapped row next to him he could sense Tiny stew and stew. Suddenly, it brought to mind something Denny remembered their mother saying once, so long ago, he couldn’t remember the scenery, maybe they were lying on a blanket on a beach.

We are all connected, she sang, as if it were a lullaby. We are all together. And we always will be.

Once he remembered it Denny couldn’t get the melody out of his head.

The movie ended and Tiny wheeled Denny out of the theater, down the long ramp shared by all the other sick or elderly, much closer to their feeble ends. For a moment Denny felt strong thanks to the healthy arms of his brother. He felt like an uncomplicated man.

We’re here aren’t we, Denny tried. Together forever. I’m glad you never became an astronaut, he laughed.

Denny felt his brother’s hands pause on the wheelchair handles.

That was kid shit, Tiny said roughly, and then he took his hands off the wheelchair. Denny tried and failed to roll the chair around or backwards, to get a look at his brother, shadowed against the foreign Florida sun. But he was awkward with the machinery and by the time he turned his brother was gone.

Mark Chiusano is the author of The Fabulist: The Lying, Hustling, Grifting, Stealing, and Very American Legend of George Santos, and the story collection Marine Park, a PEN/Hemingway honorable mention. His stories have been published in places like The Paris Review, McSweeney’s, The Iowa Review, Zyzzyva, and Electric Lit. He edits the fiction Substack Works Progress.