Childhood is Over: On Adam Ross’ Playworld

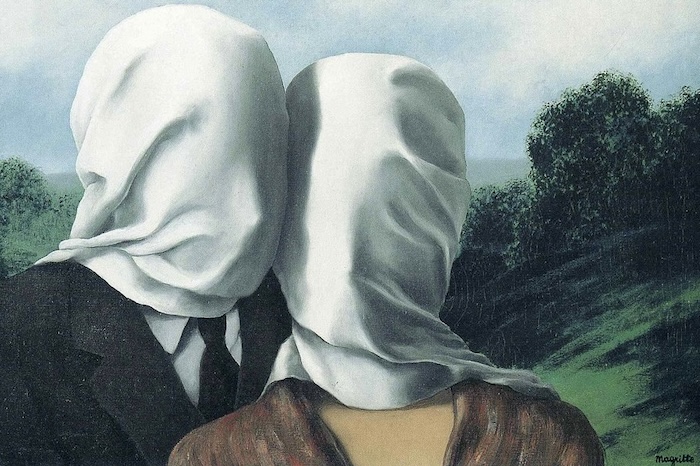

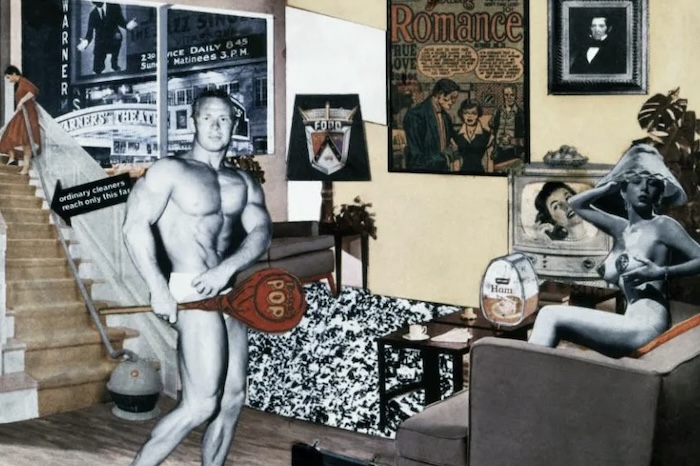

It happens suddenly, sometimes before we even recognize it, and we don’t get any say. We might be slow to acknowledge it; we might even resist it. But we can’t avoid it, or wish it away. Eventually we learn to process it, accept it, move forward. What other choice do we have? Adulthood comes for all of us, sooner or later. We might mourn what we’ve lost. Or we might be relieved that childhood — with its attendant confusion, anxiety, and lack of freedom — is over. Either way, there’s no turning back. Griffin Hurt, the young protagonist of Playworld, an outstanding new novel by Adam Ross, is a student of adulthood. Precocious and observant, he absorbs its manners and mores, familiarizes himself with its customs and concealments. The world of adults is disorienting and opaque, but he learns how to ingratiate himself with them, approximate their behavior. Like a kid trying on his father’s clothing, he might be able to convince you that the suit jacket is his — but look closer, and you’ll see the tailoring is off.